Two weekends ago, Tom and I took Otherworld Apothecary to our local pagan pride day in late September. The theme of this year’s gathering was “Ancestral Rites”, and I was asked to give a lecture on “Who are the Ancestors?” The talk was scheduled as the first of the day as a basic introduction, to be followed by talks on particulars of ancestral devotion, shrines, offerings and related topics. While not quite what I was contemplating speaking about (the influence of Spiritualism in early 20th century occulture), the lecture seemed to be well received. Following are my notes written up in long form for anyone who may be interested in my perspective and thoughts on the topic.

Hello, and welcome to East Tennessee’s Pagan Pride Day 2017. Before I get started with the lecture, while folks continue to wander in a bit, a little about me and my background. I’m Jack, and I’m half of Otherworld Apothecary, a magical shop operating since 2004, selling herbs and resins, oils, incense, potions, and other such things as well as doing consultations and magic on behalf of clients. I am a traditional witch of two admissions — an initiatory pre-Gardnerian British witchcraft tradition, and, more recently, the old Kentucky line of Gardnerian craft. I also am the Magister of a small hearth and a practitioner of Appalachian folk magic. Specifically to this topic, I’ve maintained an ancestral devotional practice for nearly two decades.

I’ve been asked today to give a talk on “Who are the ancestors?” Most pagans and magical practitioners spend a part of their ritual year, typically the fall and early winter — generally around Halloween/Samhain — thinking about and working with their ancestors. Other traditions, such as mine, work with them year round, but find these practices heightened during this season. A commonly heard phrase, borrowed from spiritualism, is that “the veil between the living and the dead is thinnest at this time”. So you’re likely to start hearing a lot more about “the ancestors” as the weather shifts and the leaves begin to change and the mist comes over the mountains.

But “who are the ancestors?” This is a question with a lot of different kinds of answers. There’s one pretty straightforward answer: the word ultimately comes from the Latin “antecessor” meaning one who goes before. Ancestor means a person from whom one is directly descended. They’re the people, now dead, whose genetic material combined in the great dance of life and ultimately gave rise to your physical body.

This straightforward dictionary answer is unsatisfactory in depth for a 45 minute talk, though, and additionally there are other answers to the question “who are the ancestors?” that depend on culture, tradition and circumstance. This is my take on the topic, drawn from my own personal practice and my informing traditions. I will also attempt to bring in lore from outside my own experience that I’ve picked up over the years in conversations with others from other traditions and perspectives.

To begin, I’m defining ancestors as “dead folks,” so, though one’s parents are technically “ancestors”, I don’t consider the word applicable to them until after they’ve shuffled off this mortal coil. There are different types of dead people, categories if you will, I’m going to discuss 6 of them and for ease of discussion I’m arranging them into 3 groups. Though these are not hard and fast or mutually exclusive groups, they’re a good way of conceptualizing. The first group is the one closest to you, and generally the easiest one to contact and start working with. These are your Blood Ancestors—your own lineage, and include 1. The Beloved Dead and 2. The Ancestral Stream. The second group is based on where you live and the culture you’re a part of; they’re a part of your place and the stories you tell and partake in. These are 3. The Dead of the Land and 4. Heroes and Saints. The last group is of interest if you’re a witch, if you have The Sight, or you’re otherwise tied into magical currents. They’re 5. the Mighty Dead and 6. The Restless Dead. I’ll discuss each of these groups in turn, and then give a few thoughts on why any of this is at all important.

1. The Beloved Dead

This is most often what people mean when they talk about “ancestors”. These are people you knew in life bound to you with love: your grandparents and great-grandparents, aunts and uncles, and may include friends and lovers. This is the easiest group of ancestors to contact and work with, and generally the most healing to do so. You know these people, what they enjoyed in life, their history and their stories, you miss them and want them to be well wherever they are now.

Often, people have a shrine to the beloved dead in their home. In southern Appalachian culture, this is fairly ubiquitous, even in homes where no one practices any kind of occult or magical work. It may be called a memory wall or memory table and is often along or under the stairs, hallway, or other liminal space and consists of photos and objects belonging to the beloved dead as well as members of the ancestral stream.

Working with these folks can involve simple practices, such as leaving flowers in a vase or a nod and prayer to your Gran for strength. Spiritual practices can also include providing vessels of fresh cool water to magnify their presence, offering special or favorite foods, and communicating through spirit boards.

2. The Ancestral Stream

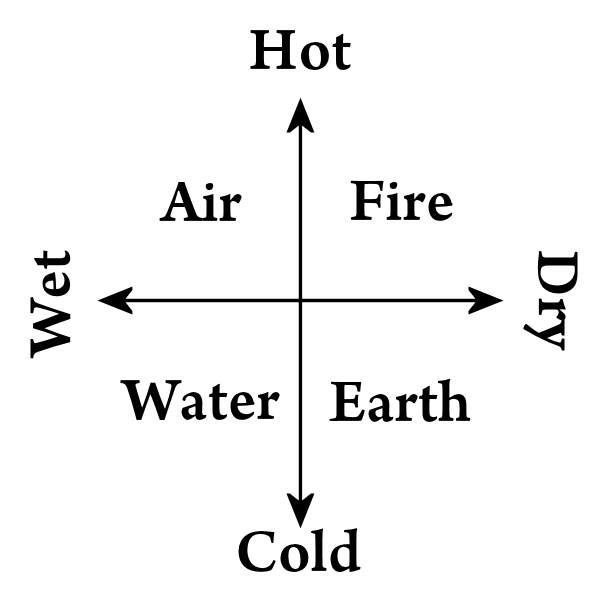

In my tradition’s worldview, and many others I know of (Germanic heathenry and other Northern European traditions, Celtic Reconstructionism, Anglo-Saxon sorcery, and others) the soul is composed of multiple parts. This soul conglomeration dissociates upon death, and the different parts go their separate ways. One of these pieces is the ancestral stream. Like the beloved dead, these are your blood ancestors, but farther back than people you knew in life. You are bound to them with your blood and body. From one perspective, outside of the here and now, you’re already dead and part of this stream.

Old lore may speak of the ancestral stream as the Distaff and Spear, which refers to the female and male branches of your family, respectively. In Germanic heathenry, particularly powerful members of the ancestral stream are known as Disir and Alfar. You may find, as you develop your ancestral practice that you’re contacted by some of these particularly powerful individuals, or specific members with which you resonate for a variety of reasons. Generally, though, the ancestral stream tends to speak as a collective, or as indistinct voices offering wisdom, guidance and strength.

3. Dead of the Land

In contrast to the previous groups, which are the ancestors of blood, the dead of the land are based on where you live and the culture of which you’re a part. For our culture, particularly, Appalachians tend to be very placed based; these are folks who lived in the shadow of these mountains and loved them just like we do. Their hearts and memories are tied to the land we live on. Your relationship with these ancestors is based in the land. You have an intimate bond with the dead buried in the land you live on. Their bodies are interred in the ground, break down into soil nutrients and are taken up by plants, which you then consume for food, medicine and magic. In times past, these place-based dead were blood ancestors, but nowadays, folks tend to live outside of their ancestral homesteads and instead the dead of the land are other East Tennesseans, Knoxvillians, and mountain folk.

The dead of the land can be powerful place based guardians. This may be one of the intentions behind the building of mounds for dead, the merging of human dead with land wights to become powerful persistent guardian spirits. In southern Appalachian lore, the first (or most recent) person buried in a graveyard becomes the guardian spirit of that place, and should be petitioned and acknowledged before any magic is performed there. Additionally, practitioners who work outside in lonely eldritch places will often meet the dead of the land at their working sites, and it behooves us to remember that they, too, are our ancestors of a sort.

4. Heroes and Saints

Another class of ancestors, based around the culture we belong to and the stories we tell and partake in, are those dead considered heroes and saints. The veneration of deceased heroes started in classical culture, where people gave offerings to particularly powerful heroes that were in the process of becoming divine and which could aid them from the afterlife. For the most part, these are localized dead who are culturally famous in a specific place, though individuals like Odysseus, Heracles, Ariadne and Orpheus are also among them. The notion of hero cults extended into the rise of Christianity where saints, many of them again powerful localized dead, were able to help those who venerate them. Saints feature in many magical traditions and spells today, like the charming traditions of magic from Ireland and Scotland (see the Carmina Gadelica and other sources), Iberian folk magic (see the work of Jesse Hathaway Diaz), and some African traditional religions.

British cultural heroes, like King Arthur, have a played a fairly large part of the modern pagan revival. They were invoked to lend their aid by Dion Fortune to save Britain from the Nazis and are also still worked with by the Gardnerian Tradition. Though modern Americans don’t really have cognates to cultural heroes like King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, or localized powerful Saints outside of Latin America, the idea can still be applied in the form of People’s Saints. These are cultural figures whose life is notable and exemplary, who may be venerated, emulated and invoked for aid in certain areas of one’s life. For instance, those working for environmental causes may declare John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, Rachel Carson and Aldo Leopold as people’s saints and invoke their aid in raising awareness of environmental issues and protecting land and resources. [I’m planning a future blog post on People’s Saints soon]. These are just a few ways that cultural ancestors are still relevant to modern practice.

5. The Mighty Dead

A fifth class of ancestral spirits relevant to those who are witches and/or initiated into specific magical lineages are those called the Mighty Dead. Gardner believed they were witches who no longer reincarnated, but instead acted as teaching spirits to currently practicing witches. In Witchcraft Today he says: “But I am told that in time you may become one of the mighty ones, who are also called the mighty dead. I can learn nothing about them, but they seem to be like demigods — or one might call them saints.” They are also sometimes termed the Hidden Company (as Evan John Jones calls them in Witchcraft: A Tradition Renewed). The Secret Chiefs or Ascended Masters of Theosophy and Dion Fortune’s Society of Light and The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn are a related concept, seen as mysterious specific teaching ancestors and guiding spirits of the order.

As a class, the Mighty Dead are practitioners of the magical arts bound to you by lineage and virtue; when joining an initiatory tradition, they’re often specifically named and formally introduced to you. This hidden company of witches guide and teach, protect and sometimes cause mischief, and help the living members of the group develop and grow. They are honored and participate in the rites because they are still a part of the circle of Art and still a part of the People. For those who work on an apprenticeship model, the mighty dead may also be part of the chain of Virtue from teacher to student down through the years. For those not of an initiatory lineage, they may still make their presence known through Dreams and spirit contact.

Critically, though this is a concept shared by many magical groups by different names, the names are not simply interchangeable. Each group or tradition has a distinct set of master practitioners who have gone before. Therefore it is useful to not jumble terminology, as Ascended Masters and the Hidden Company, for example, are the same only in concept, not in membership.

6. Restless Dead

The last class of spirits I’m going to talk about are the outliers here. They’re not really ancestral spirits. In fact, you don’t want your ancestors to end up in this category. They are the restless dead, those who in Appalachia we call ‘haints’. People have encountered and feared the restless dead since ancient times. There are all sorts of spells for protection and for laying or getting rid of the restless dead from the Ancient Greeks on down. These are people who died badly, who have unfinished business, who are forgotten, stuck, hungry. Part of the work of ancestral devotion is so that your ancestors do not end up as restless dead.

Why ancestral work?

Which brings me to the close of my talk, a few notes on why it matters.

The first answer I have to offer is simply: Because we should. Without any magical benefits or considerations of spirit contact at all, it’s human nature to remember the dead. It’s natural to want peace and light for people you love and who are now gone from this world. We owe a great debt to the people who came before us; a great many of them paved the way for us to have the life we do, in a world of more freedom and more opportunity, just as we strive to make our world better for the future.

This brings me to my second reason for ancestral devotion: increased luck. Your ancestors lived their life so you could live yours, you are the continuation of their legacy and they want what’s best for you. They want you to have a happy, full life with opportunity and love. They can help open opportunities, and smooth things in your life. Essentially ancestral spirits improve and safeguard the luck of their family and descendants.

Relatedly, your ancestors can also offer protection. This is both spiritual protection as well as protection of a more mundane nature — using your intuition to warn you about being in the wrong place at the wrong time, ward your house from fires and theft, etc.

I was taught that regular devotion to your ancestors also builds your might in the spirit world. Practice contacting the spirits of your ancestors means you will have the skills to contact people who are not your dead, but who might be helpful in some capacity. We start with those closest to us, our lives and our sphere of influence and eventually are able to interact with a whole host of spiritual entities and forces. Other spirits will also notice the might you gain from regular ancestral devotion.

Lastly, wisdom, guidance, and magic may be had from the ancestors in their whisperings if you only listen. One of my blood ancestors got me into genealogy and guides me in finding the branches of our family, their names and their stories. Another has given me recipes for healing teas a few days before I came down with a cold. I assure you, your lives and your magic will be enriched through ancestral practice.

I leave you today with a quote by the brilliant Nobel Prize winning physicist, Erwin Schrodinger. He said “No self is of itself alone. It has a long chain of intellectual ancestors. The “I” is chained to ancestry by many factors… This is not mere allegory, but an eternal memory.”