As I write this article a summer storm has blown in from the west. The sky is dark and lightning is striking towards the ridge. The wind has picked up and there’s a charge in the air. I’ve got the windows open; this is my favorite part of late summer — the thunderstorms. Years ago, I used to stay at my grandparent’s ranch during the summer. Late summer was the time for haymaking, an activity made complicated by summer thunderstorms. You need enough rain for the hay to grow but also enough sun once the hay was cut to that it could dry before being baled and put away. I can understand why charming the weather would be a useful skill.

The weather’s always had a “make or break” influence over humanity, but especially so in late summer when crops depend on rain without devastating storms. As such, magical folk throughout time have been messing with the weather for the good and ill of humanity. Indeed the only law of the Christian Empire against magic made by Constantine in 321 AD exempts magical “steps taken in country districts, that there may be no apprehension of (heavy) rain when the grapes are ripe, or that they may not be dashed to pieces by the force of hailstorms.” There are references to weather magic as early as ancient Greece, as in this quote by Empedocles:

And you’ll stop the force of the tireless winds that chase over the earth

And destroy the fields with their gusts and blasts;

But then again, if you so wish, you’ll stir up winds as requital.

Out of a black rainstorm you’ll create a timely drought

For men, and out of a summer drought you’ll create

Tree-nurturing floods that will stream through the ether

And you will fetch back from Hades the life-force of a man who has died.

You can find spells and charms to influence the weather in a ton of cultures, right up through the modern age, and I’d be writing chapters on them if I were to cover the subject thoroughly.

Wind

“I’ll give thee a wind.

Thou’rt kind.

And I another.

I myself have all the other,

And the very ports they blow,

All the quarters that they know

I’ the shipman’s card.”

~The Tragedy of Macbeth, I, iii

One of the most basic magical ways for calling up a wind is whistling. Tales in Appalachia tell of those gifted with the talent of “whistling up a wind”. Those who aren’t gifted naturally with this talent can make whistles out of alder wood to conjure the wind. Incidentally the predecessor of the Irish tin whistle, the Feadan, is made from alder wood. Maybe it’s because anyone who could charm the wind surely could charm an audience.

Bullroarers (a long flat wooden blade on a string) can also be whirled around in the air to call up the wind, especially when made of lightning struck oak (though in Cornish craft, such tools are used to call spirits). Specially made weather working brooms can be swung about your head in the same manner. Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) is an appropriate material for a broom made to stir the winds in the sky. Its pungent yellow blossoms are allied with the creatures of the air and its seeds are dispersed over great distances by the wind. Regardless of the method you choose to call the wind, make sure your hair is unbound and loose; binding and knotting are ways to capture the wind, not call it.

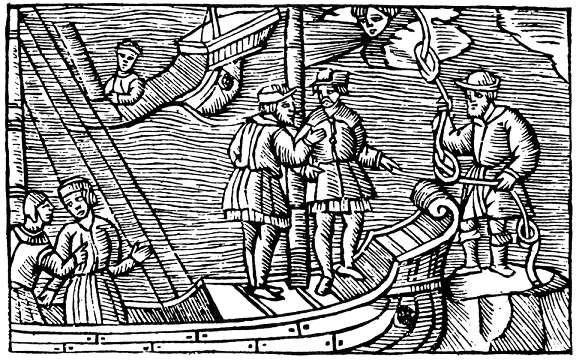

A male witch selling wind knots to a group of sailors from the Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus, by Olaus Magnus (1555).

In a woodcut (above) housed in the collections of the Museum of Witchcraft in Boscastle, Cornwall, you can see a male witch selling a wind charm to sailors. This was a common and well-known practice in pre-gardnerian witchcraft found in Devon and Cornwall. According to Cecil Williamson “There were well known sea witches selling the wind in each of the following places: Sennen, St.Ives, Appledore, Lee, Lynton and Porlock, where one found Mother Leaky still trying to flog her wind strings with their knots, right up to the mid 1930’s.”

These charms are made by going to a high-windswept place, and tying a certain sailor’s knot into a stout piece of rope to capture the wind. Winds from different directions or of varying forces may be captured using this method. Three such knots are tied in the charm, often with each containing a wind of varying strength. Traditionally this charm is then sold to sailors, but good luck getting a sailor, fisherman, or navy man to buy it nowadays.

Rain

According to De Lamiis Libre (or the Book on Witches) written in 1577 by the Dutch physician and demonologist Johann Weyer (quoted by Murray in God of the Witches), witches were said to bring rain “by casting flint stones behind their backs towards the west, or flinging a little sand into the air, or striking a river with a broom and so sprinkling the wet of it towards heaven, stirring water with the finger in a hole in the ground, or boiling hogs’ bristles in a pot.” These are all quite good and time honored methods for calling forth rain but let’s focus on three of the more practical methods for conjuring rain: more broom charms, incense, and water on stones.

As brooms can be used to stir the winds in the sky, they can also be used to bring rain. The broom end is splashed in freshwater (a river, spring, stream, or basin filled with water from such a natural source) and the drops are flung into the air over your head. Though there are many different plants that have rainbringing properties, perhaps the plant par excellence associated with weather charming (and the one best used to make a rain-bringing broom) is Heather (Calluna vulgaris). Heather is allied with the realms of mist and rain, and grows upon the wild heaths of the British Isles. It’d be an excellent herb to include in weather spells of all kinds.

In fact, a medieval incense recipe specifically to make it rain includes heather. This incense, calls for henbane, heather and fern to be mixed together and smoldered beneath the sky to bring forth rain. Many old spells recommend burning various herbs to call rain, most likely because such plants are so allied with the realms of water, mist, and rain that by burning them, you’re calling the rain to put out the fire on their beloved plants.

Lastly an old method for causing rain is to fling water or pour it through a sieve (the ones used for winnowing grain) onto a stone. The stones specified are usually ones considered in folklore to be under the protection of “the Folk” or in some way allied to old pagan religions. If you don’t happen to have standing stones haunted by “the good neighbors” close by, your hearth stone or (one specially designated) will substitute. Pour fresh water (again from a natural source) through a sieve onto the stone, or fling it using your heather broom, while praying and saying charms to bring the rain.

Protection from Storms

The last category of weather spells that need to be covered is the protection from and prevention of storms. Dame Natura isn’t all sunshine and rainbows, storms can be deadly and destructive. Hailstorms, flooding, gale winds and lightning can destroy homes and crops; there’s a wealth of traditional charms to prevent this from happening.

In the mountains of the Appalachians and the Ozarks there are a whole host of spells to prevent storms. One is to take an axe that you’ve used to chop wood and rush in the direction of the approaching storm with it over your head and swing it into the ground at the edge of your property (and presumably the edge of the field or garden that could be damaged by the storm). This will split the storm and save your land. Pocket knifes can also be used in the same manner to nail down, and thus delay, the storm or to cause it to blow over and hit elsewhere. Like most magic in Appalachia, the ability to do this is said to be one that’s taught or a natural skill some folks have (often called knack or gift).

And lastly, there are charms to protect your house and person from lightning. According to East Anglian lore, a houseleek (Sempervivum spp.), known around here as hens’n’chicks, planted on the roof protects the home from lighting, though it “must never be cut down or destroyed or its former protective power will be reversed, and catastrophe will ensue.” Other methods of protection are to plant a rowan tree (Sorbus spp.) at the front door and an elder (Sambucus spp.) at the back of the home, or to hang a pouch of mistletoe (Viscum album) from the roof.

And with that, I’m going to hang mistletoe from the roof of the porch, just in case, pour a glass of sweet tea and head outside to enjoy the summer storm.